SAY-IT-YOURSELF : THE IMPOSSIBLE FARM_

|

SAY-IT-YOURSELF : THE IMPOSSIBLE FARM_ |

|

|

WHAT IS THE IMPOSSIBLE FARM?

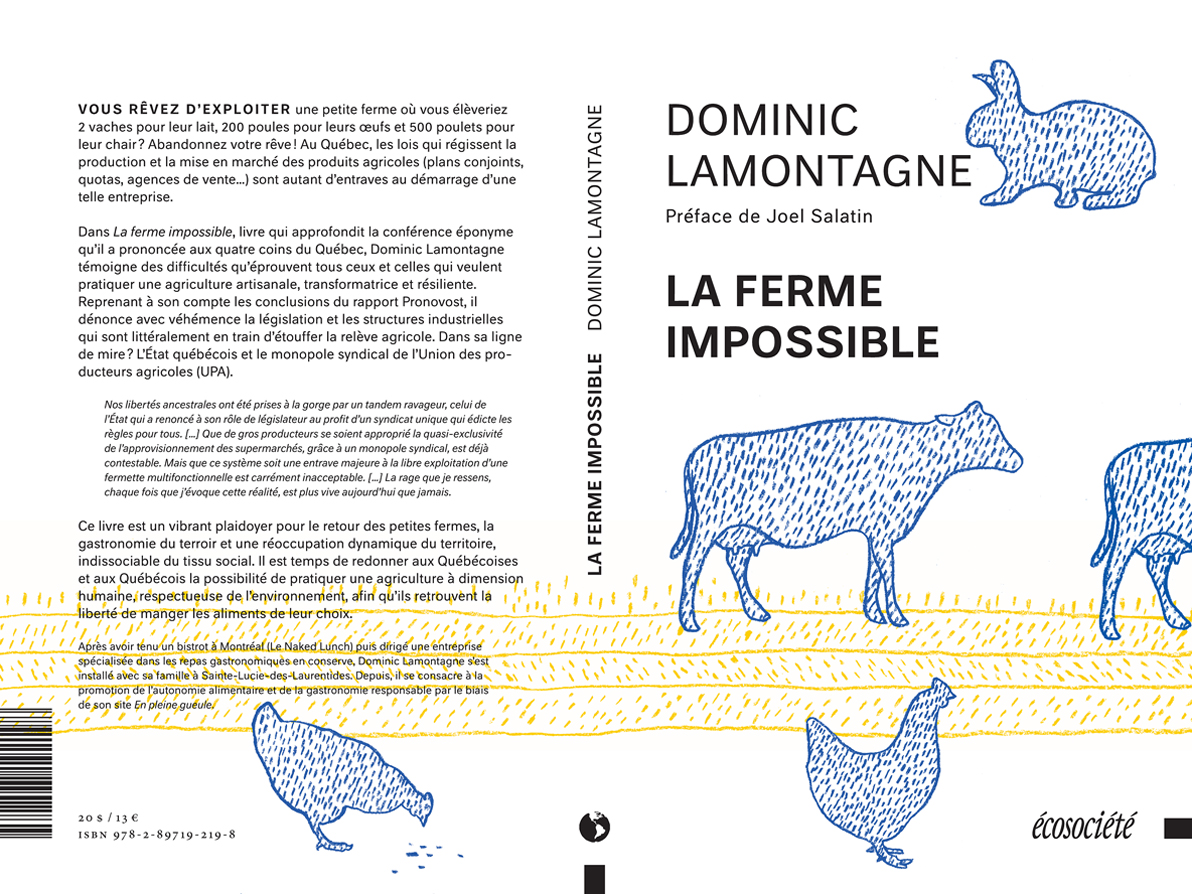

The Impossible Farm («La ferme impossible») is a french language book by Dominic Lamontagne published October 15th 2015 by Écosociété for which Joel Salatin wrote the foreword. The book describes a profitable homestead, about one percent the size of your average Québec farm, which has slowly been outlawed through years of legislative constrictions. The impossible farm described in the book raises 2 cows, 200 hens and 500 broiler chickens, grass-fed together on the range from early spring to late fall. It's a small scale, plural agro-business, which manages it's own slaughter, processing and marketing. In a nutshell, it is the beginning of a mom-and-pop's driven regional revitalization effort that favors direct (and often local, farmers market driven) sales, thus promoting resilience rather than dependence.

MORE ON THE BOOK

The book first documents the legal onslaught set upon Québec's agricultural practices during the late 1940s by the Government of Québec. Designed to profit a monopoly exercised by the Union des producteurs agricoles (UPA) (Union of Agricultural Producers), the Québec government effectively allowed and participated in the creation of an all-powerful agricultural cartel that has reigned supreme since 1972. Despite the insightful 2008 report by the Commission sur l'avenir de l'agriculture et de l'agroalimentaire québécois (Commission on the future of agriculture and agri-food in Québec, a.k.a. the Pronovost report,), which recommended a shift to a more plural, inclusive type of agriculture, no attempt to open up the cartel has even remotely succeeded thus far.

The second half of the book proposes collective re-appropriation strategies that would allow for true food sovereignty and, ultimately, local resilience. One of the cornerstones of citizen-fueled agro-resilience is the rekindling of the trade in basic produce and homemade foods which we can harvest or make ourselves such as eggs, yogurt and bread. To this end, Dominic insists we should become reacquainted with, and reconnected to, the simple arts of raising hens, milking goats, fermenting yogurt and making bread.

|

DOMINIC LAMONTAGNE: In 1997, he starts up Günt Multimedia with a friend. The partners eventually close the company, and in 2003, Dominic and his spouse Amélie start a new business specializing in vacuum-packed home-cooked meals: Gastronomie Le Naked Lunch. Soon after, the couple acquires a storefront to increase access to their products, opening up a small bistro/fine foods shop on Wellington Street in Montreal. The bistro quickly gains praise for its duck smoked meat and the shop for its high-end tinned foods (which they make on site). In 2012, the family of four trade in their hectic city life for a safe haven in Sainte-Lucie-des-Laurentides, opting for a little more authenticity and a little less glitter. They launch En Pleine Gueule in 2013, a locally operated business dedicated to the promotion of food autonomy and sustainable gastronomy. With this, Dominic hopes to contribute to the resurgence and proliferation of profitable homesteads and the love of true terroir flavours. |

|

March 3rd 2015 FOREWORD FOR THE IMPOSSIBLE FARM While Quebec's food system may be farther along the continuum toward tyranny than most in the What fascinating opposing trends: local food vs. food extortion. Both sides are growing. And is Such heavy-handed tyranny begs the question: by what authority should anyone be allowed to If a gun-wielding agent of the government can come between something as basic to human interaction Legalized extortion is no less wrong or intimidating. The marketing boards in Canada generally, and The hardest part of arguing for food choice and food freedom is trying to paint a picture of what could I don't know when I've seen a more articulate, clear presentation of the conundrum facing both Anyone who cares about a thriving integrity food system in Quebec needs to read this book, digest Joel Salatin |

The Impossible Farm in numbers

In 1950 240,000 farmers managed 145,000 farms and generated revenues in excess of 160 million dollars (the equivalent of 1.6 billion dollars today). Today, thanks to Québec's sole farmers association, the UPA, fewer than 38,000 farmers manage less than 23,000 farms but share revenues in excess of 7 billion dollars while owning 12 billion dollars worth of quotas. This cartel manages evermore money while offering continuously fewer choices to the consumer.

Modern day Quebecers are far from being free to become farmers, constrained as they are to obey ubiquitous marketing schemes, the management of which was bestowed upon the UPA a long time ago. All agricultural producers must obey strict joint plans that define every aspect of the produce they are interested in, from production methods to sales prices. And if this weren't enough, egg, chicken and milk farmers must pay a hefty price to acquire the right to produce: those infamous quotas, rarely available for sale, if ever, which have substantially the same effect (and usefulness!) of a very heavy fine on the always precarious finances of budding enterprises who must already heavyly rely on costly entrepreneurial innovations. Proof in numbers: